Hammer Throw by Emma Casburn

Hammer throw: Connections to Mythology and Significance in the Middle Ages

The sport of hammer throw is an ancient Olympic track and field event which solely consists of a thrower and a hammer. The thrower spins around 3 times in a circle, attempting to throw the hammer as far as possible. There are a few different techniques that have been used throughout history, including the use of a boulder, an actual sledge hammer and now the more modern iron- metal ball. No matter the technique used, the thrower must use a massive amount of strength as well as a sturdy balance in order to be successful at this sport. This is why men in particular have used this sport throughout history to demonstrate their physicality and showcase their valiant attitude. This essay and presentation have two main objectives: the first objective is to explore the history of hammer throw and analyse any connections it has to mythology popular in the Middle Ages. Then this paper examines why the sport has significance in the Middle Ages.

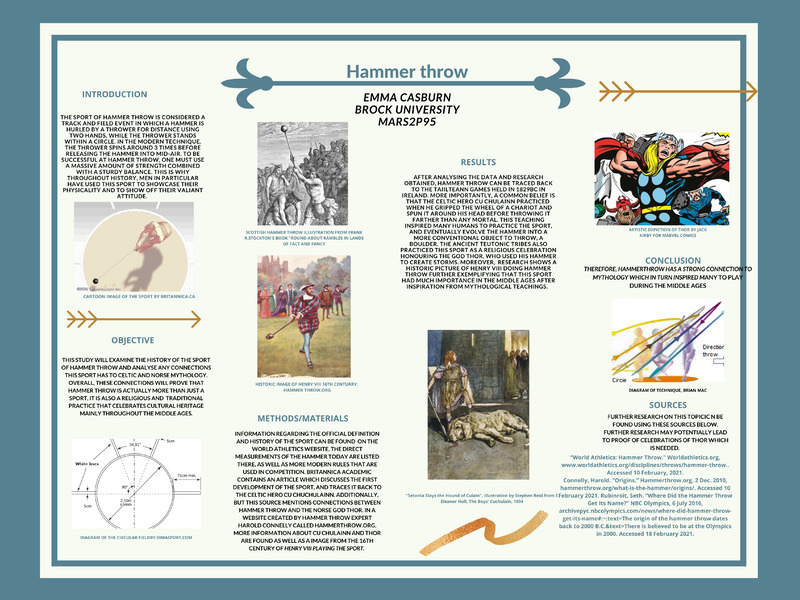

According to hammer throw expert Harold Connolly, this sport has strong historical ties to ancient Ireland. It can be traced back all the way to the Tailteann Games held in 1829 BC in Ireland (Conelly,1). The ancient Tailteann Games were funeral games and were held originally as a celebration of life for the deceased (Heffernan, 1). More importantly, however, centuries later the Celtic mythological hero Cu Chulainn, who is known as an Irish demigod and appeared in the stories of Ulster Cycle (Britannica, 1), is believed to have supposedly practiced this sport. He is believed to have gripped the wheel of a chariot by the axel and to have spun it around his head before finally throwing the wheel farther than any mortal being had before him. This event inspired many humans to practice this sport, and eventually the sport evolved to include a boulder attached to the end of a wooden handle as the object thrown in the competition (Connelly,1).

Another connection between hammer throw and mythology is located in Germanic myths and the story of Thor, who exercises his hammer to create storms of lightning and thunder (Mark, 1). Ancient Teutonic Tribes which are generally classified as a Germanic tribe held religious ceremonies in order to honour Thor (World Athletics, 1). These groups believed Thor to be the strongest defender of the Gods. Interestingly, the tribe actually practiced the sport of hammer throw in order to glorify Thor because the technique is similar to Thor’s wielding of the hammer in battles, such as the one to crash down on the heads of giants (Mark, 1).

For the final piece of research conducted on this topic, information was sought out on the significance of the sport during the Middle Ages. Unfortunately, there is not much written record regarding the sport in competitions until the early 19th century. Nevertheless, one piece of history with uique relevance to British royalty was found dating back to the Early Modern period. A 16th century painting created by an unknown artist depicts King Henry VIII practicing the sport (World Athletics, 1). However, he was actually painted with a sledge hammer in his hand. This image provides a possible reference to how the sport actually gained its official name. Soon after the Middle Ages, people were inspired by Henry VIII and continued to practice the sport with sledge hammers and competed in hammer throw in the Highland Games (Rubinroit, 1).

In summary, the sport of hammer throw, although not very well known, is actually quite notable when studying the Middle Ages and Mythology because of its strong links to the mythological heroes of Cu Chulainn and Thor, as well as its historical ties after the Middle Ages to King Henry VIII. An important thing to note is that when researching sports that were played during the Middle Ages, Hammer throw is listed there. However, other than the information found in this presentation, there is not an abundance of information available regarding how it was played in the Middle Ages. Perhaps consulting specialists such as Henry Connelly will help to determine why this is. Nonetheless, the study of the sport's origins is helpful to understand how mythology could have inspired athletics.

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Cu Chulainn". Encyclopedia Britannica, 27 Apr. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Cu-Chulainn. Accessed 18 February 2021.

Connelly, Harold. “Origins.” Hammerthrow.org, 2 Dec. 2010, hammerthrow.org/what-is-the-hammer/origins/. Accessed 18 February 2021.

Heffernan, Conor. “An Irish Race Convention? Body Politics and the 1924 Tailteann Games.” Irish Economic and Social History, vol. 46, no. 1, 2019, pp. 46–65., doi:10.1177/0332489319860629.

Mark, Joshua J. “Thor.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia, 13 Feb. 2021, www.ancient.eu/Thor/.

Rubinroit, Seth. “Where Did the Hammer Throw Get Its Name?” NBC Olympics, 6 July 2016, archivepyc.nbcolympics.com/news/where-did-hammer-throw-get-its-name#:~:text=The origin of the hammer throw dates back to 2000 B.C.&text=There is believed to be at the Olympics in 2000. Accessed 18 February 2021.

“World Athletics: Hammer Throw.” Worldathletics.org, www.worldathletics.org/disciplines/throws/hammer-throw. Accessed 18 February 2021.

Biography: Emma Casburn is a third-year student in the Concurrent Education Program. Her teachables are English and History in the Senior-Intermediate Level. Today she will be presenting on the sport of Hammer throw, and examine its ties to Norse and Greek Mythology as well as explore its importance to the Middle Ages.

How to cite this research:

Casburn, Emma. "Hammer Throw." In Reading the Middle Ages, supvr. Teresa Russo, (issue 2: The Origins of Sports and Games in the Middle Ages from East to West), Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (MARS), Brock University, March 2021, Niagara (Hammer Throw by Emma Casburn · Reading the Middle Ages: Oral and Literate Cultures · Brock University Library). Digital Scholarship Lab (DSL), Tim Ribaric and Daniel Brett.