Correspondence

The following War of 1812 letters provide first-hand accounts of the war. Many of the significant events of the war are described in detail in some of the letters, including the British victory at Detroit; the Battle of Queenston Heights, Chippawa, Lundy's Lane, and siege of Fort Erie; the American occupation of Fort George; the burning of St. Davids; and the British invasion of Washington. The effects of the war on commerce is also commented on in other correspondence. A list of assorted letters concerning the War of 1812 can be found at the bottom of the page.

British victory at Detroit

When the United States declared war on June 18, 1812, British General Isaac Brock worked to secure an alliance with the Indians of the Upper Lakes region. Brock then led a bold and successful campaign on Detroit with the help of Indian allies and their leader Tecumseh. American General William Hull surrendered Fort Detroit and his 2500 men on August 16, 1812 , even though the American troops outnumbered the British and their allies. This was a brilliant victory for Isaac Brock and for the Canadians. It was a terrible blow to the Americans.

William Henry Hall of Connecticut wrote about this is a letter dated September 2, 1812. He notes that "the Tories here chuckle much at the treasonable and infamous surrender of Hull's army, the pleasure it produced was very discernable in the smiling faces and significant grins of the Tontine patriots: but the subject will no doubt be inquired into, and whether the disaster has originated in the camp or the cabinet, I trust it will meet its reward".

Several letters to Alexander Hamilton in August, 1812, also make reference to Governor Hull and the events at Detroit. Some letters refer to an auction that was held after the surrender, and the number of prisoners still being held at Detroit and Amherstburgh.

These letters can be found in the following collections:

RG 699 Alexander Hamilton/Early Canada postal collection

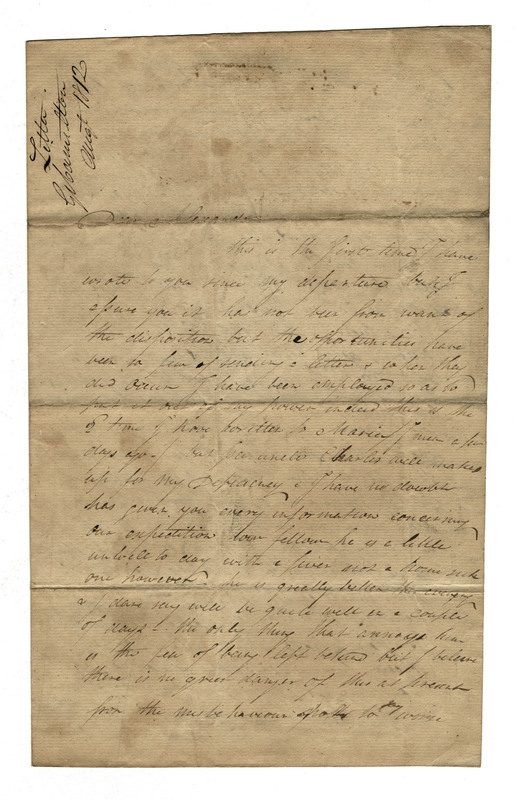

Battle of Queenston Heights

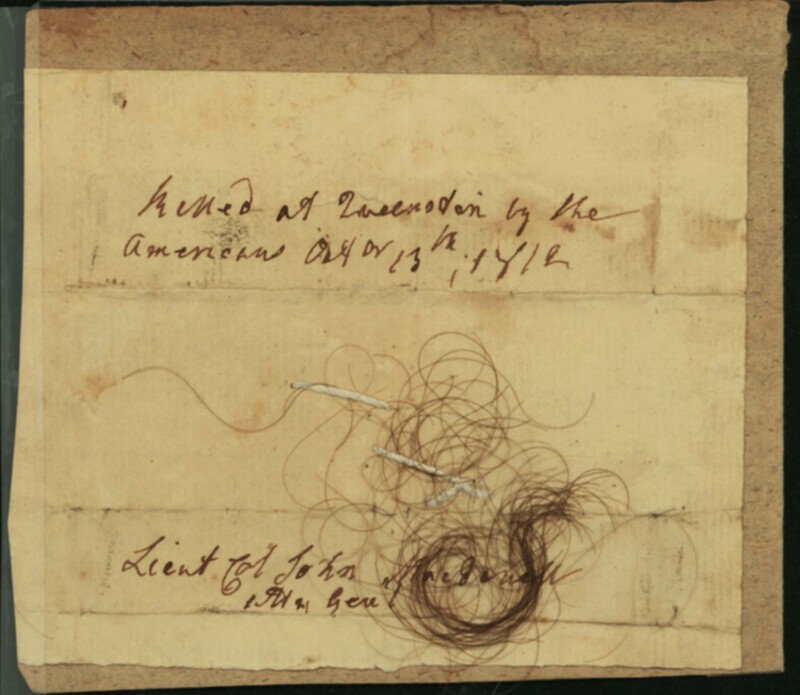

After the successful capture of Detroit, a battle at Queenston in Niagara ensued on October 13, 1812. Brock was shot and fatally wounded in the battle. His body was taken to a house in Queenston. Just before his death, it was said he uttered encouragement to the York militia, saying “Push on brave York volunteers”. Brock’s aide-de-camp John Macdonell was left in charge, but he too was killed in battle. The Americans succeeded in capturing Queenston Heights, but General Sheaffe arrived later that day with more troops and recaptured what the Americans had taken, along with about 1000 prisoners. Brock and Macdonell were buried on October 16 in a bastion of Fort George.

An firsthand account of the battle can be found in a letter to David Thorburn from W. Woodruff. Another letter from Captain John Powell of the 1st Lincoln Militia to his sister Mary provides an account of the battle and the death of John Macdonell. The letter also includes a lock of Macdonell's hair with the inscription "killed at Queenston Heights by the Americans, October 13, 1812, Lieut. Col. John Macdonell".

Several letters to Captain Peter Ogilive discuss his conduct during the Battle of Queenston Heights. Captain Peter Ogilvie belonged to the 13th U.S. Regiment Infantry. He charged the hill and helped capture the British battery but was later captured by the Canadians. After his release he wrote an account of the battle that appeared in newspapers. His account generated some displeasure among other American officers, especially John Wool, who felt that Ogilvie claimed credit for the capture of the heights.

RG 519 Letter to David Thorburn from W. Woodruff

RG 563 Letter from Captain John Powell of the 1st Lincoln Militia

RG 727 Letters to Captain Peter Ogilvie, 1813-1823

Alexander Smyth's invasion of Canada

Alexander Smyth (1765-1830) was an American soldier and Congressman. In 1812 he was given command of a brigade of regulars stationed in Niagara with the intent to invade Canada. After Stephen Van Rensselaer’s failed attack at Queenston in October 1812, Smyth took over command of his forces. Shortly after he issued a confident proclamation declaring that he would quickly conquer Canada. On November 25 he ordered troops at Black Rock, near Buffalo, to prepare to cross the river to Canada. However, he soon realized that only a fraction of the men available would be able to cross on the boats from the navy yard and decided to abandon the attack. A subsequent attempt also proved unsuccessful and Smyth realized that the untrained and ill- equipped army had little chance of success. He was harshly criticized for his failure after his confident proclamation. The U.S. government took him out of the army and he subsequently served in the House of Delegates representing Virginia as well as Congress.

A letter written by G.H. Morton to Peter P. Dox, December 8, 1812 contains a detailed description of Capt. Alexander Smyth’s invasion of Canada from Black Rock in November 1812, and the condition of Dox’s brother Captain Myndert M. Dox who was injured during the action.

Letter by G.H. Morton to Peter P. Dox, December 8, 1812

American occupation of Fort George

Fort George, situated on the west side of the Niagara River in Niagara-on-the-Lake, served as the headquarters for the Centre Division of the British Army during the War of 1812. On May 25, 1813, the Americans launched an artillery attack on the Fort, destroying most of the buildings. Two days later, the Americans invaded the Town of Niagara and occupied Fort George. They remained in the Fort for almost seven months, but suffered defeats at the Battle of Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams. Only a small number of militia remained stationed at the Fort. Fearing an attack by the British, the Americans retreated back across the Niagara River in December, 1813. The Fort remained in British possession for the rest of the War.

A letter written by Michael O'Connor, a Captain in the U.S. Army Artillery, on May 30, 1813, states that "We arrived at Niagara on the 25th May and on the 27th we attacked and carried Fort George and the village of Newark, having killed, wounded and taken prisoners better than 400 British Regulars, exclusive of Militia. The killed were 140; the wounded 160; and the prisoners upwards of 100. Our loss was trifling, say say 50-60 killed and wounded. The Enemy have abandoned all the Niagara frontier which is now in our possession blown up their Magazines and retreated with nearly 1400 Regulars towards York. They blew up the Magazine of Fort George upon us, but it did not harm any of our men. From excellent management on our part the British effected their escape. They made a wretched defense."

A letter written a few months later by Mahlon Taylor of Marcellus, New York, on July 26, 1813, comments on the American occupation of Fort George. He writes that "Mr. Wilson has just returned from Fort George, he says we have about 3500 men there, 1000 of which are unfit for duty, that there is skirmishing daily. The object of the British appears to be the bringing them out of the Fort, but that they will not be able to do, as we have suffered so recently by it is the opinion of many persons there that our troops will withdraw entirely from Canada very soon."

A letter by Jesse Duncan Elliott to Callender Irvine, dated May 29, 1813, informs him of the American capture of Fort George during the War of 1812. Irvine was the Commissary General of the United States Army at the time. These letters are available in the collections below.

A letter written by Winfield Scott, Adjt. Genl US Army, to John Haney, Dep. Adjt. Genl., British Army, shortly after the Americans had captured Fort George notes that wounded prisoners would be returned to the British army by a cartel ship. It is also noted that although Lieut. Col. Christopher Myers will not be returned, the Americans will treat him well. The letter was dated at Fort George, June 21, 1813.

RG 493 Fort George occupation letter

RG 737 Letter by Jesse Duncan Elliott to Callender Irvine

RG 814 Letter by Winfield Scott to John Haney

Battles at Chippawa, Lundy's Lane, and Fort Erie

On July 3, 1814, Major General Jacob Brown and the Left Division of the U.S. Army crossed the Niagara River and captured Fort Erie. Their plan was to meet up with the American Lake Ontario squadron and continue to raid in areas along the Lake such as Burlington, York, and Kingston. Before the British surrendered, riders were dispatched to inform British Right Division commander Phineas Riall of the attack. The following day, Brown sent a brigade under the command of General Winfield Scott north along River Road. The Americans did not get far before encountering British forces under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pearson. Riall had sent the troops to delay the American advance, thereby gaining time to gather the British troops for an engagement with the Americans.

On July 5, Riall wrongly concluded that the American force in Chippawa was largely composed of militia and felt that the British could defeat them. He subsequently engaged the Americans in battle and realized his mistake. The British eventually withdrew and removed the plank flooring from the bridge over the Chippawa River to slow the American advance. Although the Americans had not advanced far into Upper Canada, they were pleased with their victory at Chippawa.

On July 25, General Scott led a brigade of about 1000 men from Chippawa along the Portage Road towards Lundy's Lane. The British had already established their guns on the high ground at Lundy's Lane in anticipation of a possible advance by the Americans. When the British saw Scott's forces in the evening, they opened fire. The battle proved to be the most violent one of the war, with heavy casualties on both sides. The British General Phineas Riall was captured. The American Generals Brown and Scott were severely wounded and were forced to withdraw. Around midnight, the Americans left, heading towards Chippawa. They withdrew to Fort Erie, with British General Drummond following and beginning a siege of the fort in August.

The battles at Chippawa (July 5, 1814), Lundy's Lane (July 25, 1814), and siege of Fort Erie (August-September 1814) are described by Chase Clough, a semi-literate American solider, in a letter to his wife in Mount Vernon, Massachusetts, dated December 9, 1814. A letter by Joseph Blackmer dated September 30, 1814 contains an account of the siege of Fort Erie.

RG 417 American soldier's account of battles at Chippawa, Lundy's Lane, and Fort Erie.

RG 730 Letter by Joseph Blackmer describing the Siege of Fort Erie, 1814

Burning of St. Davids

On July 18, 1814, an American militia party commanded by Lt. Col. Isaac Stone marched from Queenston to the village of St. Davids. The 1st Lincoln militia defended the village, but were ultimately unable to stop the Americans. The village was subsequently looted and burned. By the time additional forces arrived to assist, most of the village had been destroyed. The burning of St. Davids was an unjustifiable act that outraged both the Americans and the British. As a result, Isaac Stone was court-martialed and dismissed from the service.

This incident is referred to in an undated and unsigned letter to the editor of the Globe. The writer comments on the lack of historical knowledge displayed by the Globe’s correspondent regarding the descendants of those who fought at Queenston Heights and the burning of St. Davids in 1813 or 1814 [July 18, 1814]. This letter can be found in the Woodruff family fonds.

RG 519 Woodruff family fonds--Letter to the Editor of the Globe

British invasion of Washington

On August 24, 1814, the British invaded Washington and set fire to the White House, the Capitol building (including the Library of Congress), and other local landmarks. This was part of the British strategy to divert American forces from the borders of Upper and Lower Canada. Instead, they looked to strengthen their forces in the Chesapeake region.

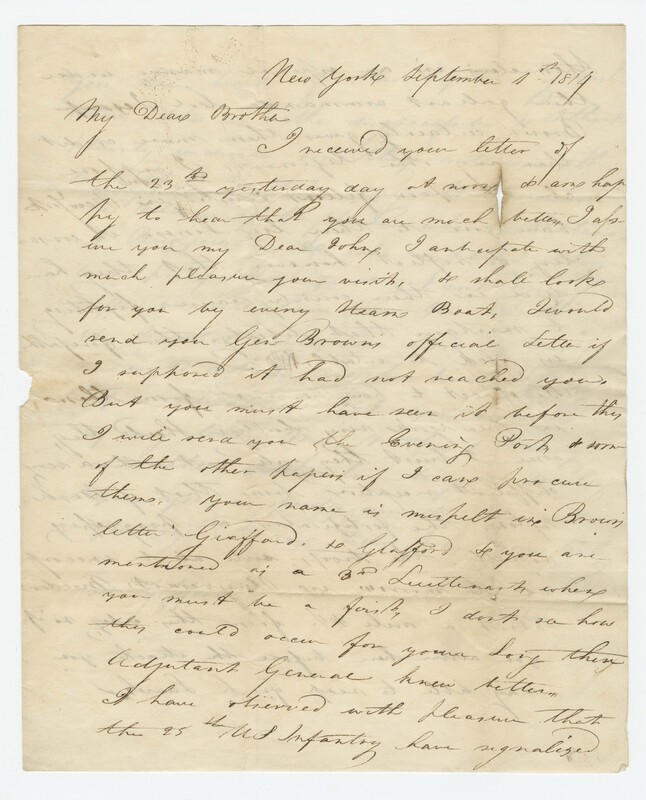

The attack on Washington is referred to in a letter to Lt. John Gifford of the 25th Infantry, from his brother on September 1, 1814. He writes that "you have heard of the capture of Washington, this is rather disgraceful and I think plainly indicates something rotten in the Cabinet. If that army who encountered the Plains of Chippewa, who beat them at Bridgewater [Lundy's Lane] and compelled them to a retreat at Fort Erie had met them far different would have been the results, the Capital would have stood". This letter can be found in the following collection.

Effects on Commerce

The War had a significant impact on trade and business. The difficulties that merchants faced during the war can be found in the correspondence of Wakeman Burritt, an American merchant who conducted his business in New York, New Orleans, Charleston, and the West Indies. He dealt with various commodities including foodstuffs, cloth, cotton, and soap.

Another American merchant, Captain John F. Kennedy, wrote about some of his difficulties in letters to his wife. Kennedy was a merchant ship Captain from Baltimore. Like other merchants of this time, his overseas shipments faced the risk of confiscation by the British, French, and Barbary pirates during the Napoleonic Wars, the War of 1812, and the Barbary Wars.

These letters can be found in the following collections.

RG 626 Merchant ship captain John F. Kennedy fonds

Other Letters

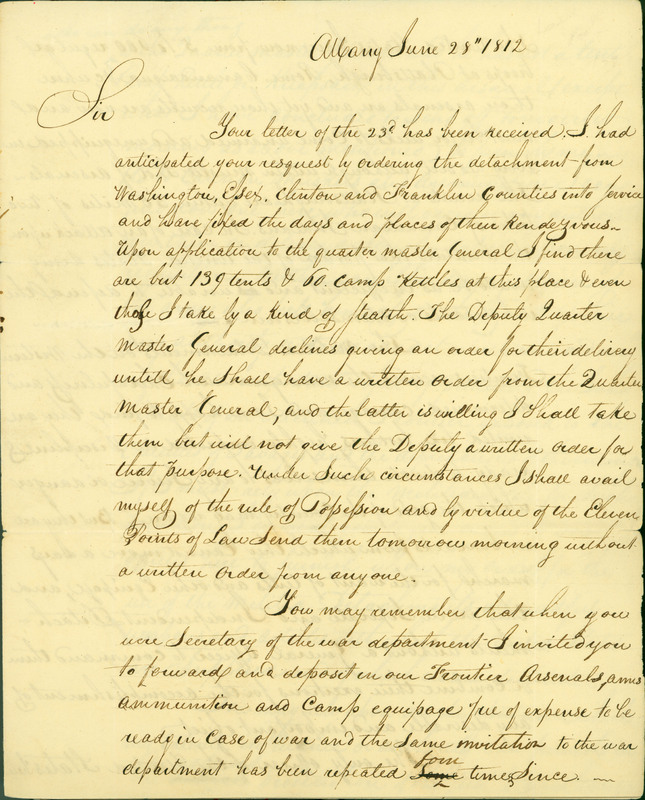

Letter from Captain A.M. Clary to H.A.S. Dearborn, May 29, 1812. (RG 447)

Letter from Daniel Tompkins (Governor of New York), to General Dearborn, June 28, 1812 (RG 412)

Letter from Sir Isaac Brock to James Fitzgibbon, July 29, 1812 (RG 582)

Letter from Major General R. Lawson, September 17, 1812. (RG 408)

Letter by Geo. Hatchey, September 22, 1812 (RG 837)

Letter from J.E.A. Masters to his uncle in Shaghticoke, New York, November 11, 1812. (RG 409)

Letters by Thomas Elwyn to his brother William, 1805, 1812. (RG 835).

Letter from Charles Larned to his sister and mother in Massachusetts, April 3, 1813. (RG 451)

Letter from John Trumbull to Lord Sidmouth, June 1813 (RG 811)

Letter by Z. Bartlett to Freeman Nye, August 1, 1813 (RG 765)

Letter from American soldier John Bentley to his wife, September 26, 1813 (RG 411)

Letter by John Pickering, November 20, 1813 (RG 840)

Letter from Lt. Henry DeWitt to Lt. John Gifford, January 6, 1814 (RG 700)

Instructions for the defence of Fort Niagara and the Frontier, March 9, 1814 (RG 769)

Letter by Josiah Hill to Thomas Stovall, March 13, 1814 (RG 838)

Letter from Matthew Clark to Henry Dearborn, July 2, 1814. (RG 685)

Letter from Lt. Col. Chewett to Ensign Kuck, September 6, 1814. (RG 404)

Correspondence of Isaac D. Barnard, 1813-1836 (RG 878)

Letter from Captain Andrew Johnson to the Committee of Invitation, June 1, 1842. (RG 635). The letter contains an eyewitness account of the death of Tecumseh at the hands of Colonel Richard Johnson at the Battle of Thames on October 5, 1813.

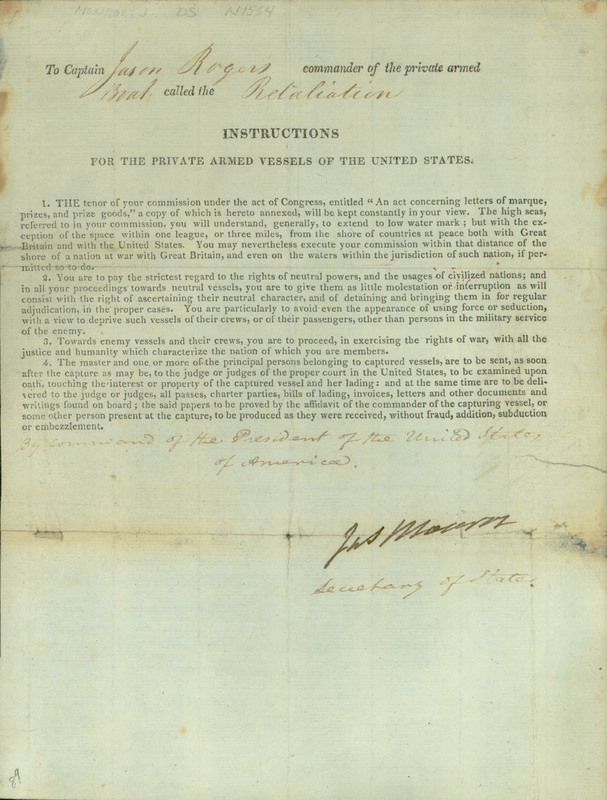

James Monroe letter of marque, ca. 1812 (RG 497)