Medicine in Anglo-Saxon Culture by Kirsten Krause

Introduction: Medicinal Practices

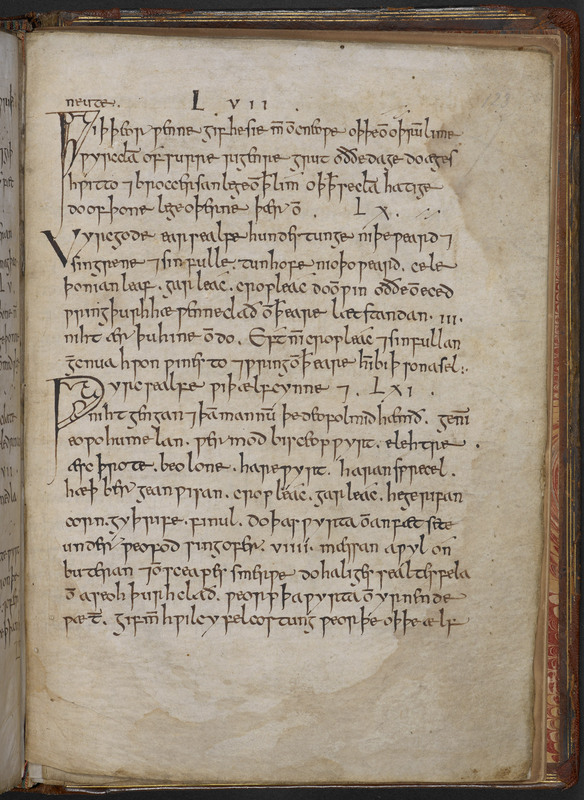

Throughout history, there has always existed in the for medicine, and manuscripts emerging from the Anglo-Saxon period highlight its importance. Physicians during this time period were known as a Laece, which translates as leech, due to bloodletting practices using leeches, as described in the manuscript Bald’s Leechbook, “Against pocks, a man shall freely employ bloodletting and drink melted butter” (Cockayne 2, 107). Ailments and remedies detailed in this manuscript range from headaches to hair loss: “If a man's hair fall out, make him a salve; take great hellebore and Viper’s bug loss” (Crossley-Holland 274). More fantastical remedies against elves and goblins are also depicted: “Make thus a salve against the race of elves, goblins and those women with whom the devil copulates” (Crossley-Holland 276), as well as remedies for protection from women's chatter: “Against a woman’s chatter eat a radish at night, while fasting” (Crossley-Holland 276), depicting the hierarchy of males in society. One remedy against an eye stye involves Bald's Leechbook has been studied and recreated by biologists and found to be an effective cure against the bacterium Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), proving almost as effective as the modern-day antibiotic Vancomycin (Harrison et al.; Cockayne 35). King Alfred, who is also mentioned throughout history in various manuscript, was also known to seek the counsel of others on the subject of medicine, due to his own ailments that plagued him (Cockayne 291; Craig 303). There have been various debates as to what he may have truly suffered from Crohn's disease, tuberculosis, or epilepsy as well as psychosomatic illnesses (Craig 303, 304). Most medicine detailed in the Anglo-Saxon. was largely herb based and used parts of animals, such as fox and crabs (Cockayne 141, 307, 309). Faith-based prayers were also used, portraying a movement from pagan ritualism towards one God under Christianity (Cockayne 141, 307, 309).

Objectives

The research conducted was influenced by an article written by Alison Hudson, who is the project curator of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts at the British Library, entitled “Science and the natural world in Anglo-Saxon England.” Researching the medical aspect and its place in Anglo-Saxon life intrigued me; these physicians perhaps will not have lays sung for them or great heroic epics written about them but they were heroes behind the scenes working to treat the ailments of the populace and passing on their knowledge to future generations as they lived through famine plague and violence (Rubin 63). They also had to contend with a populist suffering from poor hygiene as well as a lack of nutrition, evidenced by osteoarthritis and alveolar disease present in the bones exhumed from Anglo-Saxon cemeteries (Rubin 68). King Alfred is depicted as a great King; yet in Bald’s Leechbook, we can see that he seeks advice for his ailments demonstrating that like all people afflictions can happen even to a King (Cockayne 291).

Materials & Methods

The article, entitled “Signs and the Natural World in Anglo-Saxon England” by Allison Hudson, contained many useful resources for further study into medicine and Anglo-Saxon life. The most comprehensive record for medicine and its uses found in Bald's Leechbook ,which is a manuscript written in Old English between 925-950 AD in Winchester (“Bald's Leechbook”). It includes the works of Roman and Greek authors, Anglo-Saxon physicians by the names of Oxa and Dun, as well as mentioning how the Patriarch Elias of Jerusalem sent help to King Alfred for his ailments (“Bald's Leechbook”; Cockayne 291). The manuscript is made available online through the British Library, and Thomas Oswald Cockayne translated the book as Leechdoms, wortcunning, and starcraft of early England : being a collection of documents , for the most part never before printed, illustrating the history of science in the country before the Norman conquest, published in 1864, which has been made available online (featuring the Old English text of the manuscript on the left with his translation on the right side of the page). The beginning stages of scientific theory is outlined in the manuscript; medicine in the Anglo-Saxon was built upon knowledge passed down as well as through trial and error. Though they did not have the sophisticated laboratories with which to test and prove scientific methods; they did have many physicians trailing remedies for various ailments and did keep records to be passed down for future generations, like those who had come before them had done (Cockayne).

Results

By studying these sources, one can see that although medicine was not glorified, it still played an important role in society. The fact that there were remedies against supernatural beings, such as elves and goblins, as well as religious charms does highlight this mix of old paganism with a trickling of Christianity coming into play (Cockayne 141, 307, 309). Prayer is mentioned throughout Bald’s Leechbook: “To keep the body in health with prayer to the lord: this is a noble leechdom” (Cockayne 295), reflecting the role religion is starting to play in historical texts and Anglo-Saxon life. The fact that there were charms against women’s chatter was also of interest, as women are shown to speak in Beowulf, as demonstrated by Queen Wealhtheow who “welcomed the Geatish prince and with wise words thanked God that her wish was granted that she might depend on some warrior for help against such attacks” (Beowulf , Crossley-Holland 89), and who also had a role in the mead-hall festivities: “Then the lady of the Helmings walked about the hall, offering the precious ornamented cup to old and young alike” (Beowulf, Crossley-Holland 89). This is in stark contrast to what is seen in Bald’s Leechbook, as there is a negative association with women chattering amongst themselves, to such an extent that a medicinal remedy exists against it, which could highlight the hierarchy of men existing in Anglo-Saxon culture (Crossley-Holland 276). For the most part the remedies were ineffective because treatment was mainly for outwardly appearing symptoms; however, there were some effective remedies, such as the eye salve that is effective against MRSA today indicating that a handful of remedies were potent (Rubin 68; Harrison et al.). The remedy states “take cropleek and garlic, of both equal quantities, pound them well together, take wine and bullocks gall, of both equal quantities, mix with the leek, put this then into a brazen vessel, let it stand for nine days” (Cockayne 35). As science and technology advance, our understanding of medicine only grows, and it is therefore understandable that remedies from over 1000 years ago will not always be effective (Rubin 68). The fact that King Alfred’s ailments were widely known is also of interest, as typically the King is placed on a pedestal and never wants to be seen as weak in order to assert power: “Aethelstan, the King, ruler of earls and ring-giver to men, and Prince Eadmund his brother, earned this year fame everlasting with the blades of their swords in battle at Brunanburh” (Crossley-Holland 19). During King Alfred’s reign, a proper diagnosis was never made, although many scholars today feel as though he may have suffered from Crohn’s disease, which affected him greatly for most of his life, especially during the mead-hall festivities (Craig 303, 304).

Conclusion & Recommendations

The fact that one ancient remedy was proven to be highly effective against MRSA indicates that we do not always have to rely on man-made drugs and antibiotics, that natural remedies can be just as powerful (Harrison et al.). Further exploration into other remedies from Anglo-Saxon manuscripts could be recreated in labs and tested for their efficacy in order to build upon the research already carried out, providing natural herbal alternatives to harsher drugs. The fact that such a famous King suffered publicly and not privately with health issues, is highly unusual during this time when many epics and lays were created about strong warriors, who embodied the heroes’ code (Cockayne 291; Craig 303). Perhaps investigations into other well-known Anglo-Saxon historical figures and their health could be carried out, in order to see if anyone else’s health issues were public knowledge, or if health issues were glossed over and erased from historical accounts. The fact that Bald’s Leechbook contained a remedy against women's chatter is surprising as in the story of Judith, the woman is seen as the hero and liberator (Crossley-Holland 89; Black et al. 126). The role of women in Anglo-Saxon society could therefore be further investigated to see how societal hierarchy affected life during the Anglo-Saxon period.

References

“Bald's Leechbook.” The British Library, 8 Oct. 2018, www.bl.uk/collection-items/balds-leechbook. Print.

Black, Joseph, et al. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Broadview Press, 2015. Print.

Cockayne, Thomas Oswald, Leechdoms, wortcunning, and starcraftof early England : being a collection of documents, for the most part never before printed, illustrating the history of science in this country before the Norman conquest. Longman & Co, London, 1864. (See Great Britain. Public Record Office Archives.) https://archive.org/details/leechdomswortcun02cock/page/n11/mode/2up/search/prayer. Web.

Craig, G. “Alfred the Great: a Diagnosis.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 84, (1991): 303–305. Print.

Crossley-Holland, Kevin. The Anglo-Saxon World: an Anthology. Oxford University Press, 2009. Print.

Harrison, Freya et al. “A 1,000-Year-Old Antimicrobial Remedy with Antistaphylococcal Activity.” American Society for Microbiology (ASM), 6.4. 11 Aug. 2015. Print.

Hudson, Alison. “Science and the Natural World in Anglo-Saxon England.” The British Library, 22 Nov. 2018, www.bl.uk/anglo-saxons/articles/science-and-the-natural-world-in-anglo-saxon-england. Web.

Rubin, S. “The medical practitioner in Anglo-Saxon England.” The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, vol. 20.97 (1970): 63-71. Print.

See captions for photography credits; Further Web-based sites for research:

Hudson, Alison. “Women in Anglo-Saxon England.” The British Library, 25 Sept. 2018, www.bl.uk/anglo-saxons/articles/women-in-anglo-saxon-england. Web.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank The British Library for the use of the Bloodletting manuscript image, as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the MRSA infection image. I would also like to thank the National Public Radio for supplying the leech image, and Encyclopædia Britannica for providing the use of the portrait of King Albert.

_________________________________

How to cite this research:

Krause, Kirsten. "Medicine in Anglo-Saxon Culture." In Reading the Middle Ages, supvr. Teresa Russo, (issue 1: Old English Literature from Manuscript to Verse: Battles, Heroes, and Women), Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (MARS), Brock University, March 2020, Niagara (Medicine in Anglo-Saxon Culture · Reading the Middle Ages: Oral and Literate Cultures · Brock University Library). Digital Scholarship Lab (DSL), Tim Ribaric and Daniel Brett.