Story of Lucretia

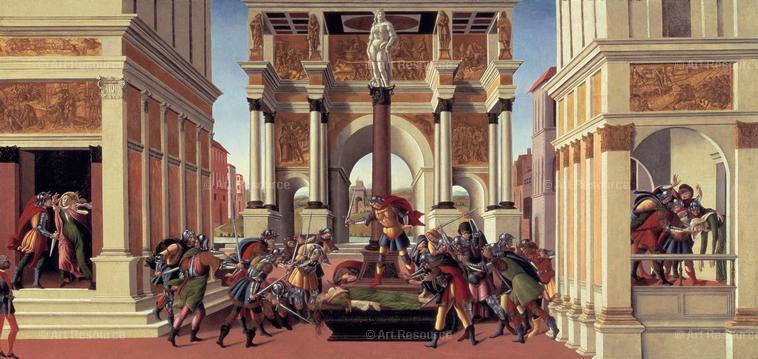

Botticelli sets the Story of Lucretia (1496-1504) in the Roman Forum Collatia, decorated with large marble and gilded buildings with relief carvings (see Appendix Image 4). The Roman myth of Lucretia tells the story of Lucretia’s rape committed by Tarquin, a “seemingly trustworthy kinsman of her husband, Collantinus”.[1] Tarquin’s punishment is overshadowed by Lucretia’s decision to take her own life to protect and restore the reputation of her husband and family after she had been violated. In another of his continuous narrative paintings arranged into three scenes, we see a series of events; in the first scene on the left Lucretia’s cloak is grabbed by Tarquin who brandishes a blade, and she is seen lifting her hands in fear. It is on this side of the composition, “in a private interior” where Lucretia’s assault takes place.[2] The second scene, on the right, illustrates Lucretia falling into the arms of her husband and brother-in-law, Brutus. Both he and Lucretia are repeated in the final and central image where she can be seen lying on a pyre with a dagger in her chest while Brutus stands behind her on a plinth, calling for her to be avenged. Brutus assumes the focus in the central scene as the heroic male leader in the face of this tragedy.

Botticelli’s piece is highly staged and theatrical. This story depicts a moment in ancient Roman history where vengeance was sworn against a tyrannical and corrupt prince and a republican revolution began. For at least two years, Florence had been without the Medici and was functioning as a Republic. The presence of Judith with the head of Holofernes in the relief over the left scene, and David as the statue atop the porphyry column, suggest that the work has political connotations. Both Judith and David were important civic symbols in Florence, depicted as protectors of the city “against mightier enemies”.[3] These Biblical figures belonged to Florentine iconography and came to symbolize the “heroic defense of republican liberty against tyranny”.[4] After the Medici’s downfall and expulsion in 1494, the Lucretia images could have been read as political allegories denouncing and condemning Medici tyranny.[5] Moreover, Lucretia’s death was considered the catalyst for ushering in the Roman Republic. Therefore, these figures together signal the emergence and protection of the Florentine Republic, which could only be won with the defeat of the Medici.

[1] Even, Yael. “The Emergence of Sexual Violence in Quattrocento Florentine Art.” Fifteenth Century Studies, vol. 27, 2002, (113-128), p. 117

[2] Even, “The Emergence of Sexual Violence in Quattrocento Florentine Art.”, p. 117.

[3] Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli, p. 268.

[4] Dressen, “From Dante to Landino”, 335.

[5] Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli, p. 269.