Battle at Queenston

After the stunning victory at Detroit, Brock returned to Niagara. He had planned to invade New York State before the Americans received reinforcements, but his plans were dashed by an armistice that had been arranged by Lieutenant General George Prevost and General Dearborn. The armistice allowed continued use of the Niagara River by both the Americans and British, and Brock could only wait helplessly while reinforcements and supplies were brought to General Van Rensselaer's army in the United States.

General Stephen Van Rensselaer was a Major General in the New York State Militia. But he did not have a great deal of military experience. He was a politician from a wealthy family. He had never commanded troops in battle but was nonetheless given command of the army at Niagara. The reinforcements he received during the armistice boosted his force considerably. At its peak, Van Rensselaer's army consisted of more than 6000 men including officers, regulars, and militia. His plan was to cross the Niagara River at Lewiston and take Queenston. After a failed first attempt on October 11, Van Rensselaer decided to proceed on October 13.

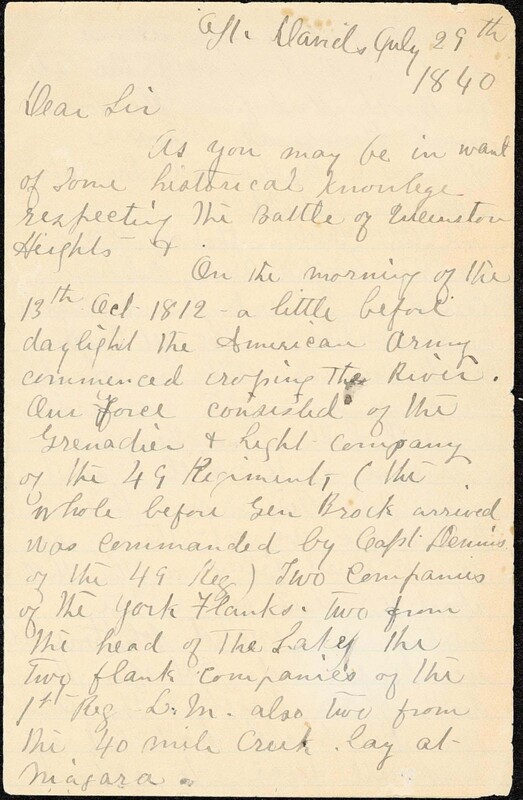

Brock was aware of the failed attempt to cross on October 11, but was not sure if this was a ruse to distract from an attack elsewhere. However, when a British Major crossed the Niagara River on October 12 to arrange an exchange of prisoners from a recent raid, he became suspicious of the Americans and believed they were planning to cross again. The Americans insisted that nothing could be arranged for a couple of days, and several boats were hidden near the shore under some brush. When this intelligence was relayed to Brock, he decided to dispatch orders for the militia to be ready for action.

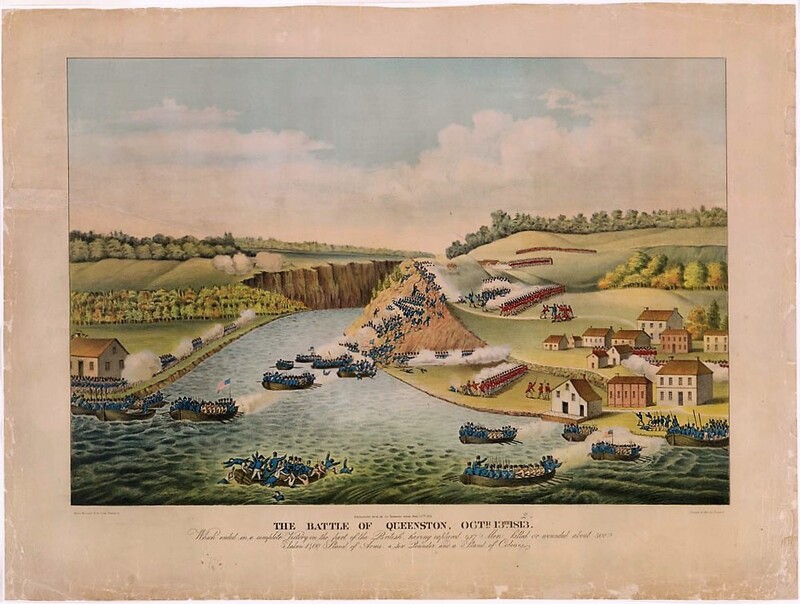

In the early hours before dawn on October 13, thirteen American boats crossed the Niagara River from Lewiston. Ten of the boats landed at Queenston. The remaining three were swept downstream by the current. Once the boats landed and discharged the passengers, they returned to the American shore to retrieve more men. British troops fired relentlessly on the Americans.

Brock was at Fort George when the Americans crossed. It is unclear if he was awakened by the artillery or informed of the news by a rider on horseback. Unsure if the attack was real or a diversion, he quickly left to to investigate leaving orders for some of his aides to be awakened and follow him. Along the way, he encountered a portion of two flank companies of the 3rd York Militia and ordered them to follow. It may have been at this point that Brock famously uttered the words "Push on the brave York volunteers". Brock arrived in Queenston around dawn. Around the same time, the Americans were able to ascend the slope and seize control of the battery on Queenston Heights which had caused much carnage to the Americans. It is thought that Brock may have sent a message to Major General Sheaffe at Fort George to bring as many reinforcements as possible. He then set out to recapture the redan on the heights from the Americans.

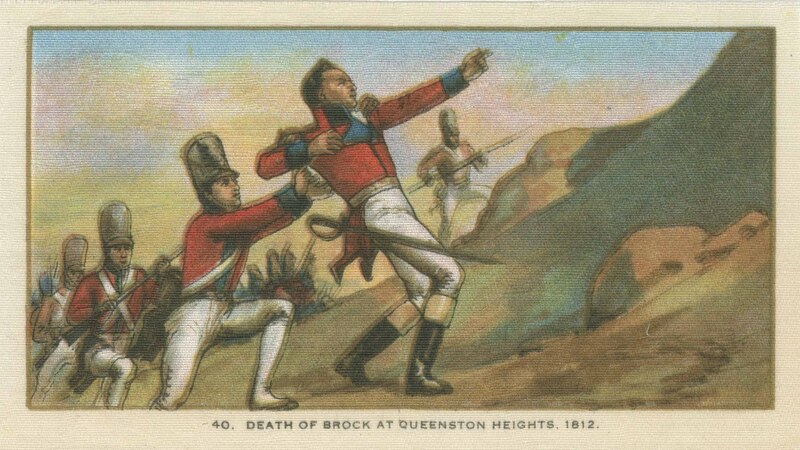

This lithograph of the Battle of Queenston Heights depicts Brock dying in the foreground among the York Volunteers and First Nation warriors with American troops in the background. Engraved in the frame (not shown here) are the words “Push on York Volunteers! Brock’s dying words”. While it has become a common belief that these were Brock's dying words it seems unlikely. Brock was not with the York Volunteers when he was shot, and it is thought that he died almost instantly from his wound. The coat he was wearing, which shows where he was shot, is in the Canadian War Museum.

Brock charged the hill with men from the 49th Regiment of Foot and two companies of militia. During the assault, a musket ball grazed Brock's left hand. But he continued the attack only to be shot down at close range. He was an easy target because of his tall stature, colourful officer's uniform, and drawn sword leading his men in the charge. He was struck in the chest and died almost immediately. His body was quickly taken from the battlefield and concealed in a nearby home.

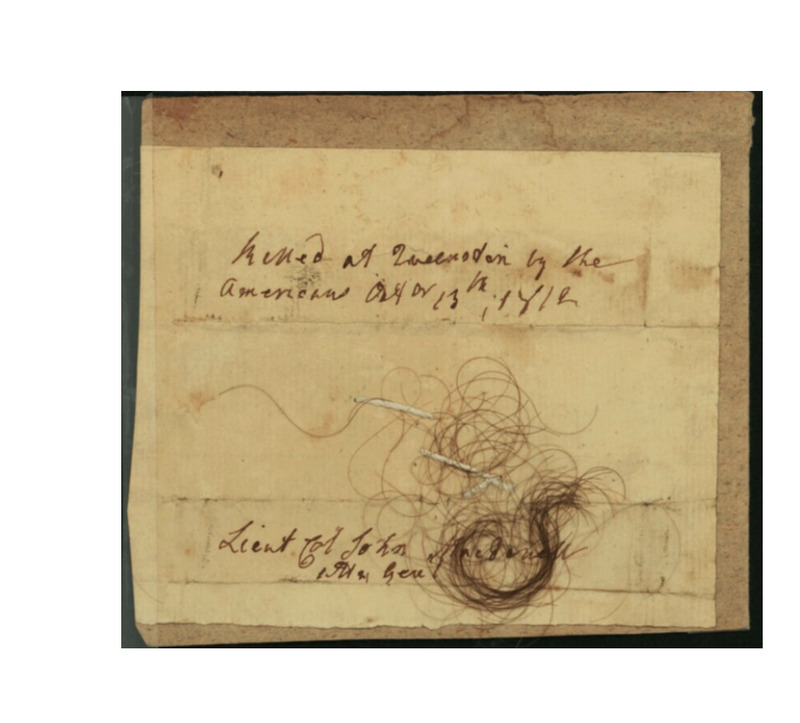

Lietuenant-Colonel John Macdonell (Brock's aide-de-camp) and Captain Williams led a second attempt to retake the redan. They were significantly outnumbered by the 400 Americans on the heights. The British had only about 80 men, most of whom where militia, but were able to mount a strong advance. The Americans were pushed back to the edge of the gorge on which the redan was located and it seemed that success was possible. But the British attack faltered when Macdonell was shot and fell from his horse. At almost the same time, Williams suffered a severe head wound. Macdonell was removed from the battlefield and died the following day. The Americans were able to regroup and hold their ground. The British retreated to a farm near Vrooman's Point about a mile outside of Queenston. It was about 9:00 in the morning.

The British continued to fire on the Americans from Vrooman's Point and the Americans did not attempt to drive the British from their position here. Some reinforcements began to arrive from Fort George as well as about 80 Grand River Six Nations warriors under the leadership of John Norton. Norton made a clever tactical decision to lead his warriors up the escarpment to the west of Queenston. It was not only an easier climb, but the woods provided an ideal cover as they approached the Americans. The warriors played a critical role at this point in the battle using guerilla-style tactics to prevent the Americans from establishing a firm defence until General Sheaffe and reinforcments arrived.

Meanwhile, General Van Rensselaer appointed Lieutenant Commander Winfield Scott to take command on Queenston Heights. Most of the units on the heights were incomplete and disorganized. Only about a thousand of Van Rensselaer's men had crossed the Niagara river and many of the regulars and militia were abandoning their positions to find their way back to American soil.

It took Major General Sheaffe several hours to gather reinforcements and devise a plan of attack. It was just after 3:00 p.m. when Sheaffe led a British advance against the Americans. Like Norton and the Grand River warriors, he chose a route to the west of Queenston that shielded them from American fire. The combined forces included men from the 41st Foot and 49th Foot, Captain Robert Runchey's Company of Coloured Men, John Norton's warriors, and the militia. Sheaffe commanded more than 900 men. He arrived with his army on Queenston Heights and once his men were in place, he gave the order to advance. The Americans became pinned between the allied forces and the cliff and soon began to retreat.

The Americans were in a dire position. The militia in Lewiston heard the gunfire and war-cries of the warriors and refused to cross the river claiming that they were not legally required to fight on foreign soil. Van Rensselaer was unable to rally the men who steadfastly refused to fight. Hundreds of the Americans at Queenston Heights had taken shelter in the woods instead of fighting. Scott surrendered to the British fearing that the continuation of hostilities would lead to a massacre by the Grand River warriors who had lost two chiefs in battle. After the surrender, there were about 900 American prisoners and around 300 killed or wounded. The British and Canadian forces and indigenous warriors had about 125 killed and wounded.